When Silent Expression Is Heard by the World: Cheng Lu and His Echo Bridge

Repost an interview post by china.com.

I was interviewed by the China.com Technology Channel about Echo Bridge, an AI‑driven communication concept my team and I designed for people who are deaf or hard of hearing, as well as those with speech impairments. The article below is an English rendering of that feature story, adapted slightly for the blog post. (Source: China.com, Google translate.)

In hospitals, banks, and classrooms, most people can complete basic communication simply by saying a few sentences. For many deaf and hard‑of‑hearing people, and for people with speech impairments, the absence of suitable assistive tools often means they have to explain their situation bit by bit through writing or typing. The very same tasks end up demanding far more time and energy.

Echo Bridge is designed to change exactly that moment.

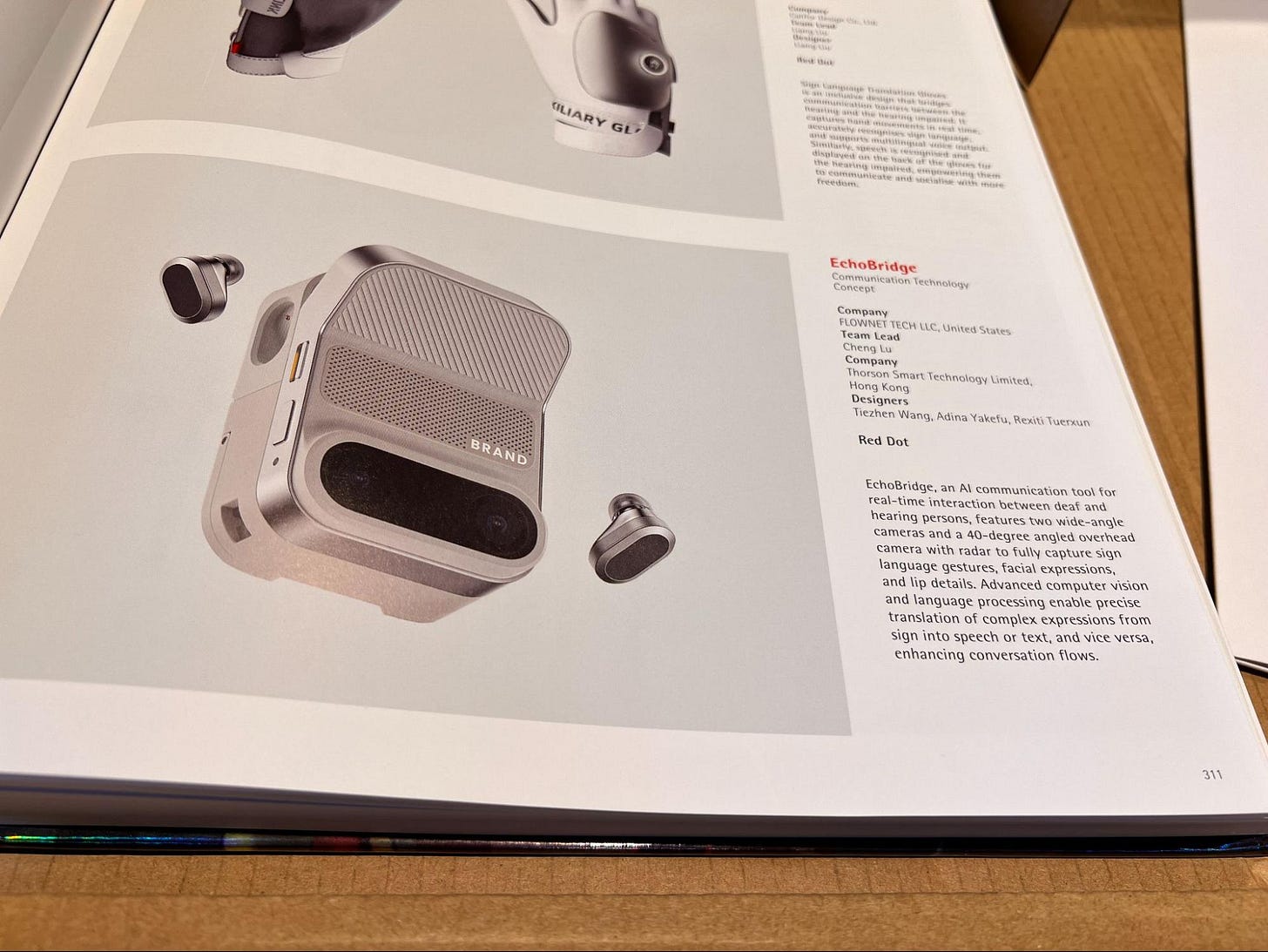

Winner of a 2025 Red Dot Design Concept Award in the “Communication Technology” category, Echo Bridge is Cheng Lu and his team’s attempt to explore the frontier of assistive technology. Cheng, the project lead, has long been active in developer and open‑source communities. Over the past decade, his work has focused on building developer ecosystems and promoting new technologies, helping more developers understand and adopt them. This time, however, the product is aimed at a relatively niche group: people who are deaf or hard of hearing, a community that is easily overlooked in everyday life.

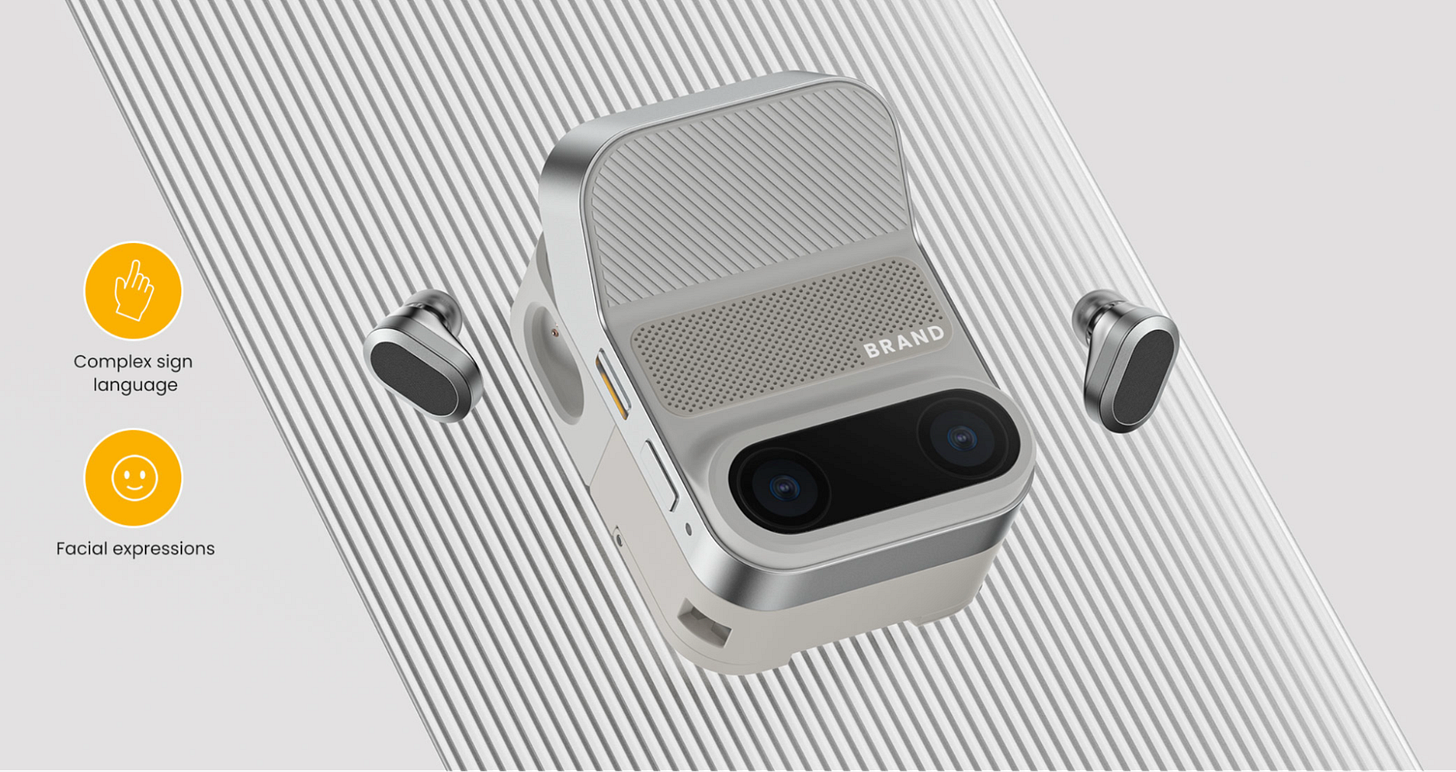

Visually, Echo Bridge is a compact set of devices: a desktop base unit paired with two wireless terminals. The base unit is equipped with two wide‑angle cameras and one overhead camera with radar, allowing it to “see” the user’s gestures, facial expressions, and lip movements from multiple angles at once. For sign languages, these details are not “auxiliary information” — they are part of the language itself. True silent expression is usually formed by the combination of hand movements, facial expressions, and mouth shapes together.

Once these images are captured, the AI system in the background takes over. Using computer vision, it recognizes movements and expressions, and then combines them with language models to translate these silent expressions into text or speech for the hearing party. Cheng describes it as “an interpreter sitting between the two sides,” whose role is to pass on the meaning from both ends as completely as possible.

Unlike many hardware products that have already entered the market, Echo Bridge remains at the concept‑design stage. There is no mass‑production data yet, and systematic user testing has not begun. Cheng is candid about this: “Right now it is a ‘sketch’ we’ve drawn, not a product that can be put into use immediately.” In his view, the significance of this “sketch” is not only in presenting the rough outline of a product, but in placing a clear direction on the table. “We want to first surface this problem, map out possible technical routes, and let more people see them. In the future, if we find the right partners, or more people are willing to join us in refining it, then when the time is right, we can turn it into a real product.”

Looking back at his motivation, he says the starting point was actually quite simple:

“Over the past decade or so, my work has mainly been about technical evangelism and ecosystem building for developers — helping more developers and companies adopt new technologies faster and better, so they can use these tools to improve productivity and create more valuable products. That in itself is already very meaningful.

For most people, new technology usually means a slightly faster phone, clearer photos, more features in an app. All of that is great; at its core it just makes life a bit more convenient. But for some people with hearing impairments, a well‑designed technology product offers more than convenience; it determines whether they can speak for themselves.

In the past, they often had to rely on family members to interpret for them, or to write everything down. Many subtle feelings were hard to express fully, and the other side could not really hear them. If a tool like Echo Bridge could help them ‘translate’ what they want to say more completely, so that others can understand them on the spot, that shift — from almost not being able to speak to finally being properly heard — is, to me, something very concrete and deeply valuable.”

Red Dot’s recognition of Echo Bridge comes not only from its technical concept, but also from its design attitude. The physical design deliberately avoids the cold aesthetics of medical equipment, leaning instead toward familiar consumer electronics. It looks unobtrusive on a desk and does not feel “special” in the hand. The design team hopes it will be a tool anyone can use naturally, rather than a marker that constantly reminds its user, “You are different from others.”

In Cheng’s view, accessibility should not be treated merely as a narrow niche market, but as a litmus test for the deeper character of technology. “Technology is inherently meant to serve the public; that universal value is the basis for its existence,” he adds. “At the same time, we hope more of the tech community can pay attention to this space, so that the same technologies are applied more often to groups who are easily overlooked, creating products that truly change their lives.”

Echo Bridge may still be only a concept design, but it has already sent a clear signal: in an era of rapidly advancing artificial intelligence, technology can certainly continue to serve large‑scale everyday needs, and it is also fully capable of bringing more meaningful innovation to the field of accessibility. Cheng and his team hope this small concept can become a starting point — one that prompts more people to see, reflect on, and even step into this area, working together to build a dependable bridge for those “silent expressions” that have long struggled to be heard.

(Text by Zhang Han)